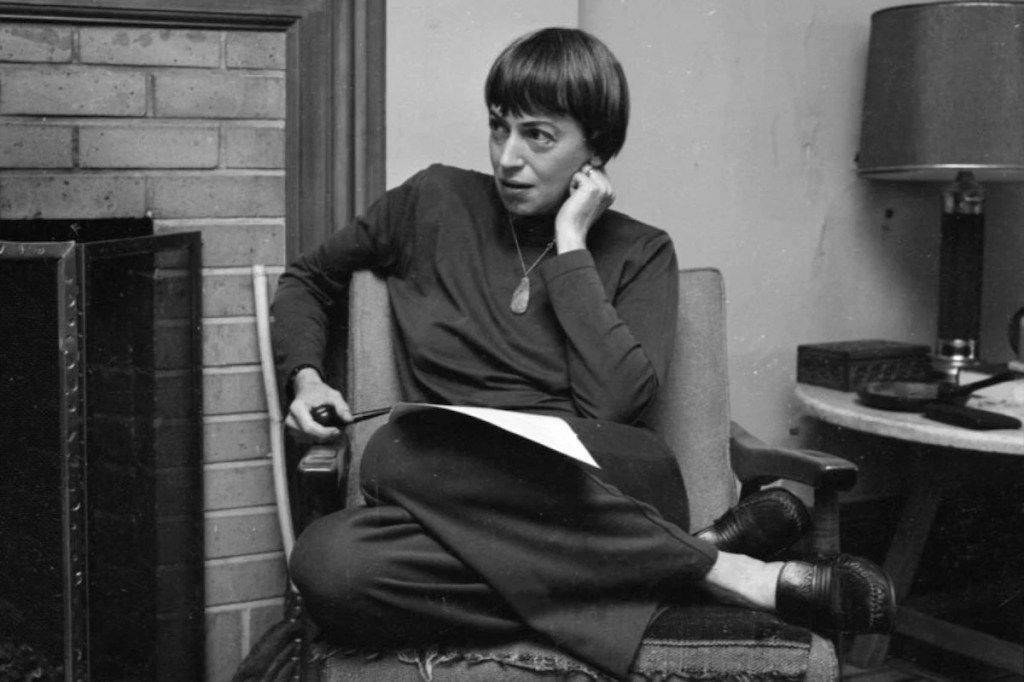

My current thought about Ursula K. Le Guin is that for someone so ubiquitous her work is strangely underrated. Le Guin was an institution for a long time before her death. She’s now so beloved that any reminder of the fact she was a part of a living, thriving, thinking community for several decades can seem jarring – Samuel Delaney spent how many words critiquing The Dispossessed? and Farah Mendlesohn would still rather talk about Diana Wynne Jones today too huh?

All the same, it’s fair to say that when people talk about Le Guin’s work they’re really talking about the run of novels for adults and children that she completed between 1968 and 1975. I say this without a hint of fannish bitterness because The Left Hand of Darkness and A Wizard of Earthsea are a fine pair of books to base an appreciation on, and anyway most authors would be lucky to have so much attention given to their work. Still, the more I read and re-read Le Guin’s later works the richer it feels to me and the more I worry those who enjoyed the early Earthsea books and The Dispossessed might be missing out.

When I finally come to write about Always Coming Home and Lavinia, two of Le Guin’s richest and most bewildering novels, I hope to do so in a slightly more thorough style. Today, I’m thinking about The Shobies’ Story, part of a trilogy of tales collected in A Fisherman of the Inland Sea in 1994. I recently re-read this story in the American Library edition of Le Guin’s Hainish tales, having first encountered it in the second volume of The Unreal and the Real.

The first few pages of The Shobies’ Story are the sort of thing you don’t want to encounter at the end of a mentally/physically demanding day, when your eyelids seem to be more susceptible to gravity than any other part of your body. The style is familiar and formal, a steady procession of unusual names and alien cultures. The tired reader will have to double back on to keep straight whether Tai and Betton are from the ruined Terra of The City of Illusions or ice cold Gethen from The Left Hand of Darkness. If they’re not minded to enjoy this sort of thing they might no even bother to read beyond these first few pages.

Don’t get me wrong, this is a fine mode whether it’s played straight or for laughs, and the early parts of The Shobies’ Story are a solid example of the form. As usual with Le Guin, light-eyed readers will find telling details in even the most straightforward of passages:

Churten theory was the main topic of conversation, evenings at the driftwood fire on the beach after dinner. The adults had read whatever there was to read about it, of course, before they ever volunteered for the test mission. Gveter had more recent information and presumably a better understanding of it than the others, but it had to be pried out of him. Only twenty-five, the only Cetian in the crew, much hairier than the others, and not gifted in language, he spent a lot of time on the defensive. Assuming that as an Anarresti he was more proficient at mutual aid and more adept at cooperation than the others, he lectured them about their propertarian habits; but he held tight to his knowledge, because he needed the advantage it gave him. For a while he would speak only in negatives: don’t call it the churten “drive,” it isn’t a drive, don’t call it the churten “effect,” it isn’t an effect. What is it, then? A long lecture ensued, beginning with the rebirth of Cetian physics since the revision of Shevekian temporalism by the Intervalists, and ending with the general conceptual framework of the churten. Everyone listened very carefully, and finally Sweet Today spoke, carefully. “So the ship will be moved,” she said, “by ideas?”

Here we have both a clash of character and a clash of culture that does not entirely define the former by the latter. We also have the introduction of the real theme of the story, the seemingly absurd notion that ideas alone can move us from here to there if they find enough agreement. Le Guin works this around a science-fiction framework which encompasses at least one sustained anarchist revolution and thus also the possibility that this example hasn’t taken the galaxy by storm overnight. If the rest of the story followed this pattern there would be a lot to recommend it. As the story moves on, however, its style shifts to better capture the radicalism of the technological conceit: a form of transport that can take you anywhere all at once, but which may cause reality-shredding shifts in what “anywhere” means from one person to the next.

Reading this story again, a little tired but not quite ready to let the night win, I bewildered my partner by saying “Fuck!” out loud in a way that would normally mean “I’ve left the oven on” or “I forgot to pay the window cleaner” or maybe “I accidentally sold one of the cats to the postie”. What can I say, I’ve seen people try to write science fiction in the style or Virginia Woolf before – hell, I’ve tried to write it myself! – but to be reminded that such a thing is achievable was more shocking to me than transporting directly from my bed to the office could ever be.

Gveter tried to find another word, but there was none. He perceived outside the main port a brownish, murky convexity, through which, as he looked intently, he saw small stars shining.

He found a word then, the wrong word. “Lost,” he said, and speaking perceived how the ship’s lights dimmed slowly into a brownish murk, faded, darkened, were gone, while all the soft hum and busyness of the ship’s systems died away into the real silence that was always there. But there was nothing there. Nothing had happened. We are at Ve Port! he tried with all his will to say; but there was no saying.

The suns burn through my flesh, Lidi said.

I am the suns, said Sweet Today. Not I, all is.

Don’t breathe! cried Oreth.

It is death, Shan said. What I feared, is: nothing.

Nothing, they said.

Unbreathing, the ghosts flitted, shifted, in the ghost shell of a cold, dark hull floating near a world of brown fog, an unreal planet. They spoke, but there were no voices. There is no sound in vacuum, nor in nontime.

There is a metafictional conceit at work in all of this, of course. If our characters are to return home they must use the technology best placed to contain their different perceptions, a technology that might look a lot like The Shobies’ Story itself. In Neil Gaiman’s hands this would be mere self-congratulation, but Le Guin embodies the effort involved in the text and elucidates its social implications: even on a spaceship crewed by explorers of different cultures who have agreed to work in a non-hierarchical manner, it will take more than good social intentions to reconcile the needs and perceptions of those involved. The jump from the possible to the actual will still look impossible from considerably closer than here. The blurring of expository, lucid science fiction into modernist fragmentation makes this difficulty explicit, and asks the reader to experience it alongside the characters.

To home in on that Woolf comparison a bit further, what the style and theme of the late sections of The Shobies’ Story really remind me of is the crashing monologues of The Waves:

“‘Like’ and ‘like’ and ‘like’–but what is the thing that lies beneath the semblance of the thing? Now that lightning has gashed the tree and the flowering branch has fallen and Percival, by his death, has

made me this gift, let me see the thing. There is a square; there is an oblong. The players take the square and place it upon

the oblong. They place it very accurately; they make a perfect dwelling-place. Very little is left outside. The structure is now visible; what is inchoate is here stated; we are not so various or so mean; we have

made oblongs and stood them upon squares. This is our triumph; this is our consolation.

In Woolf’s novel, this technique achieves a sense of unity through fragmentation, dramatising a series of consciousnesses that are travelling in different directions but which still point to a shared origin. The Shobies’ Story reverses the trick in miniature, making music from disharmony. It’s a hell of a trip.

Having embodied a sense of difficulty in this first exploration of her “Churten” concept, Le Guin went on to explore the ramifications of perceptual imperialism in Dancing to Ganam, and made use of a Japanese fairy tale to explode the conflict of internal possibilities in ‘A Fisherman of the Inland Sea’. I’ve been thinking a lot about these difficulties while facing up to the political moment, and how we might not just survive it but use the crisis to build the coalition we need to make a world we can keep living in. When we talk about listening and coming together it can sound like we are calling for some sort of bogus TV debate, where hate speech is given equal space to human rights. This triptych of stories from Le Guin doesn’t just point to a more radical sort of task, it goes some way to letting it play out on the page.

Rather than reprint the whole thing here, I’ll quote Le Guin’s contemporary and rival Samuel R. Delaney’s closing thoughts from his contribution to the Why I Write? series in the name of brevity:

There is a difference between dialog-and -respect and imposition-and-domination. And if many more of us don’t start to understand those process effects and their imperfections as well as their successes, soon, directly or indirectly, we’ll kill each other and ourselves off. It’s that simple…

Given that we have separate brains, that we can “communicate” as much as we can is quite amazing – but don’t let your amazement make you forget that “communication” begins as a metaphor for an effect (a door that opens directly from one room to another, a hall that leads from one place in a building to another) but is thus neither a complete nor an accurate description of many things that occur with sound-making and sound-gathering.

There is strength in our mass, power in our unions, but only so long as we can understand the limitations of our bonds as well as their potentialities.

One response to “Hey Now, You’re (An) All Star”

[…] on from yesterday’s Le Guin theme, the first post in a series where I pick my top three tracks from a random record, in this case the […]

LikeLike