“We have to recognize these demons when they arise and utilize the formulas to dispatch them, which is what magic does. Magic has a time-honored, thousands-of-years old methods for dealing with the type of demonic energies that arose at Altamont, for instance. A bunch of highly-trained warrior magicians at Altamont would have defused the situation; unfortunately they weren’t there. And there is the failure of the ‘60s written right in front of us.“

Grant Morrison, interviewed by Jay Babcock for Arthur Magazine, 2004

It sounds like an excuse to say I watched Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99 by accident, but there we are. What else are you supposed to do when the socially permissible housework has already been done and you’re waiting for the latest episode of Better Call Saul to materialise?

I’ve not seen last year’s Woodstock ’99 documentary, HBO’s Peace, Love, and Rage, but I’ve read more about it than I’ve read about many things I profess to love. This is just one of the perils of being Extremely Online.

Of all the articles and tweets I consumed, Craig Jenkins’ piece for Vulture stuck with me. Its commentary on the Peace, Love and Rage’s mixed handling of the sexual assaults was convincing, and Jenkins raised some interesting questions about the broader musical/social argument of the piece:

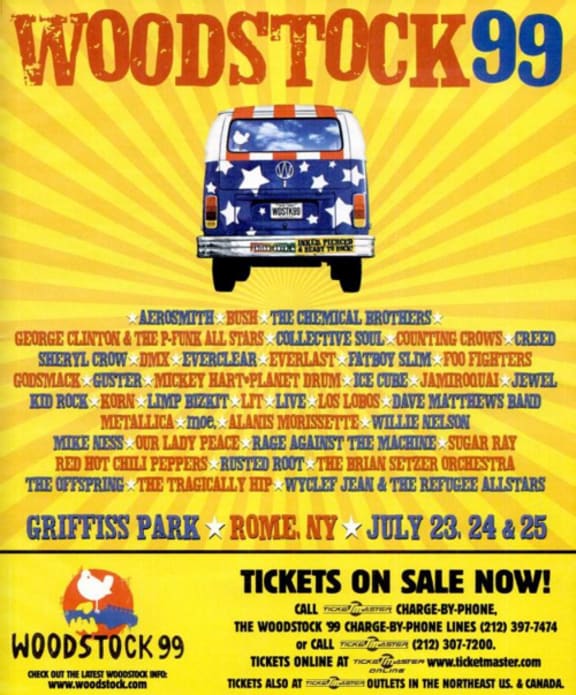

“The thing is, only four nu metal bands played Woodstock ’99. (Twice as many jam bands were present!) And concurrent tours with lineups more firmly rooted in the angrier stuff didn’t suffer similar fates. In 2000, Metallica’s Summer Sanitarium Tour, which Korn and Kid Rock opened, did not burn, and neither did the 1999 Family Values Tour…. When Coachella is touted as the ethical alternative to the corporate shortsightedness forcing the riot that turned Woodstock ’99 into a historical tragedy, it is never mentioned that the Indio production has had its own well-documented struggles with sexual assault in its crowds. [Peace, Love and Rage] makes the events of that weekend in Rome, New York, seem like a confluence of horrors that could only have sprung from the climate of 1999, when in reality, we see a little of its hell every year.”

By the sound of it, Neftlix’s Trainwreck documentary might be even worse in its handling of sexual violence. I didn’t tally up the amount of time taken to discuss the rapes that happened on site but if it’s about even with the time spent showing the tits of adolescents then it’s still less of a part of the fabric of the documentary. The sexual assaults are only dealt with at the end of part three, with little detail or follow-up to the statements given by talking head organisers. The teenage tits, meanwhile, are interspersed throughout the documentary – ostensibly we are meant to gape in horror, but more often than not it feels like we are just supposed to gape.

The cultural argument of Trainwreck is loud but rarely clear. We recognise certain sounds from previous discussions but it’s hard to be sure how much work our expectations are doing, and this doesn’t seem like an accident. A decent amount of time is given over to suggesting nu-metal bands were responsible for the violence, but unless one counts archival footage of Korn and Limp Bizket as evidence of inarguable calls for destruction, it’s not entirely convincing. As Craig Jenkins points out, this was hardly the only show in town when it came to the commodification of white male rage that summer.

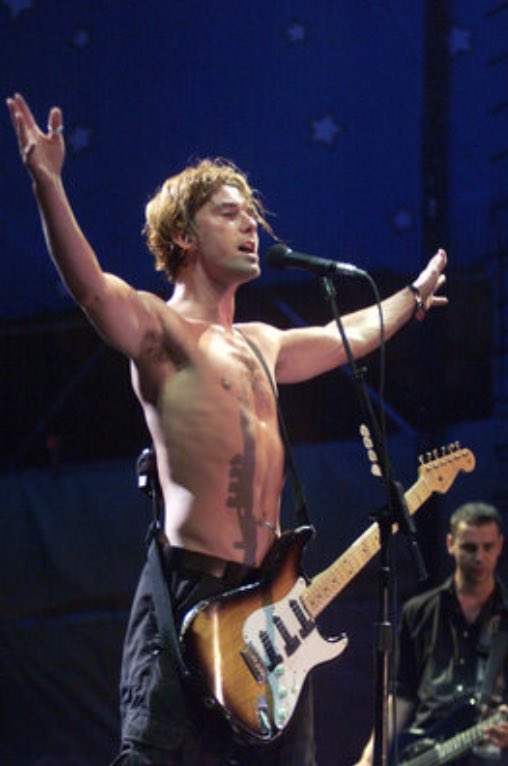

Organiser John Scher puts the blame on Fred Durst riling up the crowd to ‘Break Stuff’, but whatever we might think about some artists’ handling of their social responsibilities, it’s easy to see such comments as an attempt by Scher to divest himself from all culpability. Elsewhere there seems to be a suggestion that artists like Bush and Jewel were working magic to keep the crowd under control, and that things might have been different if people hadn’t been quite so entranced by the endless supply of drop-d riffs on offer.

Much is made of the way Gavin Rossdale’s naked torso and slightly less rawkus rock brought the crowd back to the peace, love and understanding vibe of Woodstock ’69 at the end of the first night. Even granting the idea that this was Bush’s default setting – it wasn’t: their mode was a sort of put-on/put-upon anguish, a prettiest sadboy at the party horniness that set them apart from their influences – as Jenkins points out, the numbers just don’t add up. What’s clear from the performance footage in Trainwreck is that Korn, Limp Bizket and Kid Rock could move a huge crowd in summer 1999. What’s not clear is that this dark power is so all-encompassing that it could cancel out the combined powers of Alanis Morrissette, Dave Matthews Band, Our Lady Peace and Mike Ness.

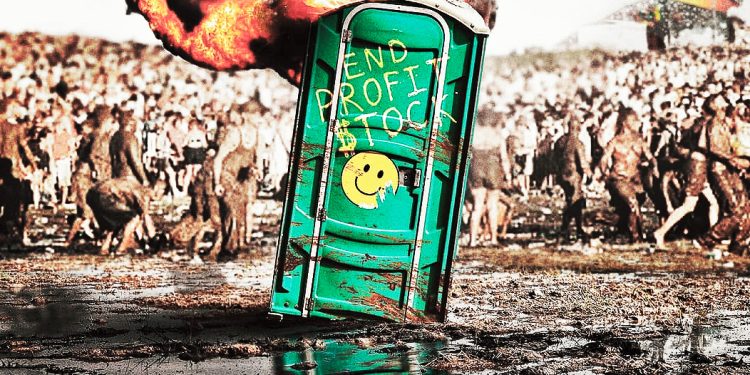

The third and most convincing thread of Trainwreck has to do with the material conditions on sight at Griffis Park on that weekend in July 1999, and with the decision making that made such conditions possible. That it’s still possible to come away from the documentary wanting more on these topics is not exactly an endorsement of the finished product. There’s a better documentary to be made here, one that focus on the real magics at play on the day – the greed and hubrisitic incompetence of select group, sure, but also the broader framework of exploitation and misogyny that made all of this shit possible, and which is not limited to one small moment at the end of the last century. That documentary would be worth making, but while Trainwreck makes some of these arguments, in the end it’s just a less pernicious example of the thing it wants to criticise: a crude bit of alchemy where sensational misery is turned into a payday, an excuse to group up and tut at “herd behaviour” without really investigating what that might mean outside of the screen.

One response to “Angles and Demons”

[…] recurring scene in the Trainwreck: Woodstock 99 documentary involves bands and crowd members alike taking shots at the big pop acts of the time. We see MTV […]

LikeLike