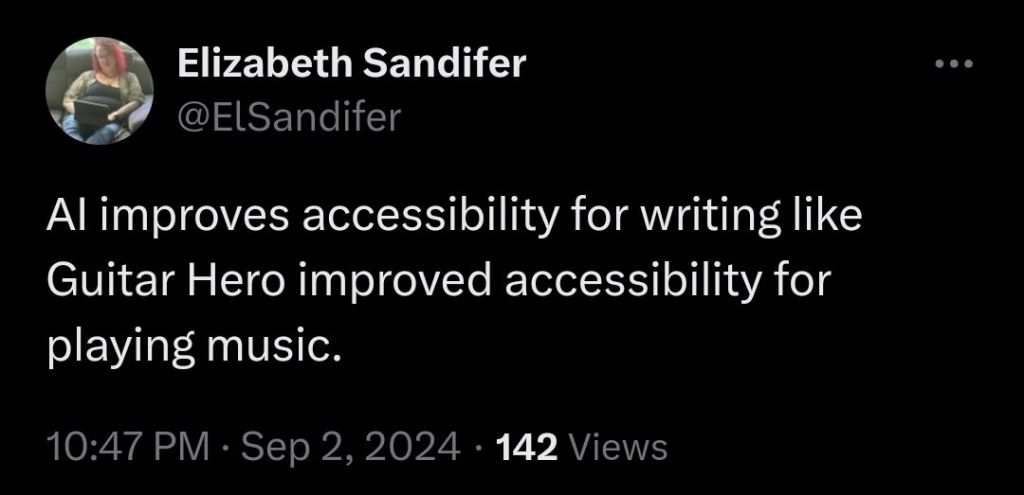

“AI improves accessibility for writing like Guitar Hero improved accessibility for playing music.”

Another day, another attempt to avoid a pointless scrap on social media! I understand what Elizabeth Sandifer is getting at with this joke, but the comparison still bams me up. More than it should, obviously. The gaming franchises of the 2000s don’t need defended from every lighthearted mention, and yet…

Guitar Hero and the like and offered a fun, if heavily mediated, way to engage with existing culture; they did not, at any point, pretend to be a shortcut to production itself. Or a tool for accessibility. Generative AI, meanwhile, presents lack of engagement as production.

Kieron Gillen had a better grip on what the likes of Guitar Hero were selling back in the day:

Guitar Hero is about tricking you into thinking you’re playing guitar. You press the buttons and strum with the flipper… and the appropriate noises appear. The power of Harmonix’s system is how – even at the basic levels – they’ve judged the correct number of inputs to make you feel as if what you’re doing has some connection to the music that’s emitting from the speakers. That by waggling your fingers in a certain way, that riff screams out. You stop waggling your fingers… it stops. You’re playing the music.

You know you’re not. But you certainly feel like it.

“You know you’re not” alone makes all the difference here. Combine it with Kieron’s uncanny explanation of how this fantasy maps on to traditional game design via “input fallacy”, and you’ve got a fresh perspective on games and rock music:

Games trick you into thinking you’re doing something more difficult and interesting than you actually are. In Prince of Persia, you may just be pressing a single button, you’re rewarded with a powerful leap from the lead character. The fallacy is your brain connects your action to the animation – that it was you that did that, thus you should feel the rush of reward. Your actions created that reaction. In a real way, many of the best games are based around this, and games which fail to make you feel as if your on-controller actions connect to your onscreen actions are dismissed out of hand. This is why – say – Dragon’s Lair connected with gamers less than the similar period’s Defender, despite the spectacular difference in the visuals. In Dragon’s Lair, there was no real sense that you were controlling Dirk the Daring. In Defender, your slightest twitch was magnified spectacularly on screen. In one, you watch the hero. In the other, you are the hero.

Watching/being the hero is a rock’n’roll fantasy that predates and survives Guitar Hero. It means living through the changes in a song in a way that’s totally attuned to what the artist is doing, even if you don’t really know how they’re doing it. Generative AI takes us on the opposite journey. Instead of translating processes of production and appreciation into a new form of play, it seeks to cut them out altogether.

This is where Elizabeth Sandifer’s gag gets gummed up, as far as I can see. Her joke implies that both generative AI and Guitar Hero offer the fantasy of making art without labour. I’ve already argued that this misunderstands the appeal of Guitar Hero. Let’s go further: the comparison reinforces the very misunderstanding of AI it seeks to correct.

Creating art by prompt isn’t the fantasy of being an artist. That’s what AI shills want you to believe, and as Sandifer is trying to show here, it’s a nonsense. The true fantasy of generative AI is of a different order, and we should be clear about that even when we’re making dumb jokes at its expense. The real fantasy of AI is that you, too, can be a loudmouth studio exec. You want giant spiders in your Superman movie? No need to provide Kevin Smith with an anecdote, sir. Nowadays you can just mash a button and the shite will flow right into your living room.