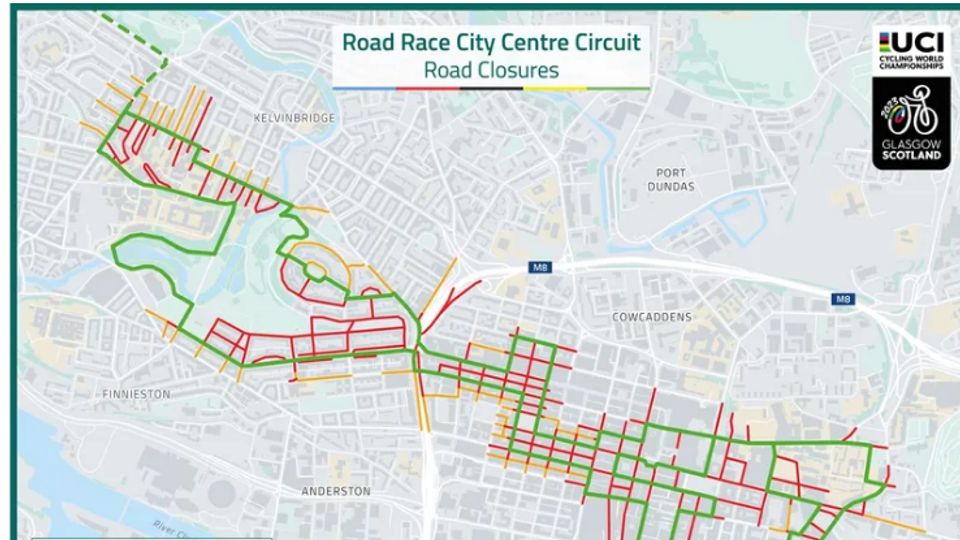

On Saturday 12th August I made a mistake: I crossed the river Clyde when there was an international cycling tournament in town. I’d had some experience of this the week before, when I’d skipped round heras fencing and made my way to Buchanan bus station in the early hours of the morning on my way to Fife. That had been a simple task: lycra phantoms were racing around the city centre but their numbers were limited and there were no security staff telling you when you could cross the road. The biggest obstacle to health and happiness was a guy still clearly munted from the night before who was running a different path to the same destination as me. He screamed at the lycra phantoms to fuck off out of Glasgow, he cheered them on, the shouted incomprehensible things at strangers and at one point decided to bust out some rap lyrics that were no appropriate for a man of his skin tone while crossing the road. He got on a different bus than me in the end. I relaxed.

The week of 12th August was a different story. No relaxation possible: every road a G4S cow pen, every street backed up with people, many of them more enthusiastic for the racing than me, all of them still annoyed. Going into town was an avoidable choice for many of us, you’d imagine, but while you were waiting it was hard not to feel churlish. Churlish and exposed. Despite open air not being Covid’s most competitive environment, I could still feel its spikes on the back of my neck in the crowd.

At one point it occurred to me: I’d wished for Glasgow city centre to be more bike friendly and somewhere, unseen by me, one finger had curled on a haunted monkey paw. The cycling competition was temporary, a minor annoyance. It also twisted cycling into an anti-motorist’s parody of the city designed for the car, where everything must pause to allow the endless flow of traffic and commerce through the city: goods travelling back and forth, assets burning up in real time, turning to rust around the drivers, cracking and re-cracking the roads as they go. Of course, even in its current state of decay the city centre channels pedestrians into commercial rat runs but – and we’ll come back to this in a minute, in a round about way – those are relatively easily avoided on foot. For all my penned-up huffiness, the cycling tournament was objectively less harsh on the city’s lungs and wallet than your usual traffic, the best efforts of some sponsors aside. Its aggravations came down to the fact that it formalised the controls that enforced its dominance over the urban environment. Cars don’t need a G4S goon squad to dominate the flow of the city, they do that through a combination of pure speed and physical/social weight you don’t want to fuck with.

***

Somewhere between my first cheerful visit to the land of the lycra phantoms and my second troubled one, I got to talking with a friend about what happens when bicycles hit the pavement. The friend in question has a nervy rescue dog, you see, and while they’ve worked hard to make sure he stays calm when bikes race past, the sudden appearance of one in his realm – the pedestrian realm – still sets him off into a scrappy panic. He’s not wrong, poor thing. Whether mounted by a lycra phantom or by a fellow punter, a bicycle is still a fast moving vehicle and cannot obey the same logic as the denizens of pedestrian space. Whether you’re walking alone or with a dog, pushing a pram or using a wheelchair, you can react to the tiny changes in what’s happening all around you at a pace that’s suitable for human thought. This is, in my view, the magic of simply walking down the street.

I don’t mean to elide the differences between these varied users of pedestrian space, of course. Even from my own limited experience, I know how different it is to make your way around the south of Glasgow on foot and while pushing a wheelchair, and how cars can break up your experience of the city even when they’re sitting unoccupied on the pavement. Still, I think the basic point is true. The pace of pedestrian life varies, but within a spectrum where it’s possible to make accommodations.

Another pal of mine insists that pedestrians should walk on the left hand side of the pavement, arguing that this is how he was told to do it at school. For me, this makes no sense. The joy of walking in a busy street is that you can navigate the whole space, so long as you’re attentive to those you’re sharing the space with. The risks of collision or dickhead behaviour are real, and often realised, but surely the etiquettes of motion can be looser in these zones, more accommodating of the realities of shifting interest and attention? Some exceptions apply, but otherwise you can follow the vectors of commerce or you can follow other currents, so long as you take care not to tread on everyone around you or block the way as you go.

The trick, then, is to build roads safe for cyclists, and to build reliance on cars out of urban spaces wherever possible. A fast moving cyclist is still a force to be reckoned with, but if that was the only force rattling through our urban environment on a regular basis we wouldn’t need a crew of G4S employees to keep us safe or our environments fit for humans and dogs alike. We could shop there, sure, but we could do a lot more while we were at it, and with healthier lungs to show for it.

***

The reason I went through town on August 12th was so I could help with a canvassing session in Maryhill. The trip through the west of the city was a pleasure for the most part. There were barriers and lycra phantoms and G4S guards in some areas, but the density was lower, and once you got past Byres Road it was possible to enjoy the full range of the city’s streets.

I was particularly transported by my walk up Queen Margaret Drive. Some of my best friends lived there before and after our time at University, but I don’t know anyone who lives there now. The kebab shop has been replaced with a joint that looks like it serves a range of Italian food without ever quite filling the hole a kebab shop pizza can fill. The fashion trends of students have come round to the point where they now dress like they might have a year or two before my time in the area. And so on.

It’s fully possible to experience the past overlayed on the present like this, with a layer of distortion provided by all the times you weren’t there to see it, when passing through at speed. I’ve done it myself. It’s undeniably a more dimensional experience when you’re able to dictate what you pay attention to and for how long though.

Canvassing – that is, chapping people’s doors to chat them up for a cause, in this case a party political one – is an uneasy way to go about talking to people in a big city. Even doing it in the least pressurised way, outside of an active election campaign, you can feel the destination rushing to meet you. You ask questions about local issues. If you’re not full of shit you take them on: I’m in the middle of setting up a meeting with a local councillor to pick up on traffic issues someone raised with me on another session last Thursday. In the end, everyone involved knows that you’re trying to drive up support, or at least get a sense of where that support lies.

After I finished with my canvassing session on August 12th, and once I’d made my way back through town, now with the added difficulty of football traffic on the comically limited subway system, I wondered whether my pissy mood had made me a bit pretentious. Was it mebbe a bit rich to present the pavement as not just a space of fractional democracy, but as an actual time machine too? This made me think of Samuel Delany’s Time Square Red, Times Square, as so many things do. In particular, it got me thinking about his interest in “contact”:

It is not too much to say, then, that contact—interclass contact—is the lymphatic system of a democratic metropolis, whether it comes with

Samuel R. Delany, …Three, Two, One, Contact: Times Square Red

the web of gay sexual services, whether it comes through the lanes of heterosexual services (and such gay and straight services include but are in no way limited to heterosexual and homosexual prostitution!), or in any number of other forms (standing in line at a movie, waiting for the public library to open, sitting at a bar, waiting in line at the counter of the grocery store or the welfare office, waiting to be called for a voir dire while on jury duty, coming down to sit on the stoop on a warm day, perhaps to wait for the mail—or cruising for sex), while in general they tend to involve some form of “loitering” (or, at least, lingering), are unspecifiable in any systematic way. (Their asystematicity is part of their nature.) A discourse that promotes, values, and facilitates such contact is vital to the material politics as well as to the vision of a democratic city. Contact fights the networking notion that the only “safe” friends we can ever have must be met through school, work, or preselected special interest groups: from gyms and health clubs to reading groups and volunteer work. Contact and its human rewards are fundamental to cosmopolitan culture, to its art and its literature, to its politics and its economics; to its quality of

life.

Canvassing is a poor substitute for contact, but that makes sense. Working to get a few people elected to broken institutions so they can break themselves trying to get a few cycle lanes built is a poor substitute for politics. As Delany notes right after the previous excerpt, “Relationships are always relationships of exchange”, and meeting people in this context fundamentally limits the scope of these exchanges in the way that being on the road limits the ways you can interact with other humans and the landscape around you.

A light contradiction, then, to spend your days engaged in a limited form of conversation in the hopes of rebuilding the city to allow a wider range of possibilities, be they relational, spacial or temporal. Especially when you end up pissed off with a skewed version of one of those possibilities along the way: apologies to the lycra phantoms, aside from the transphobia I’m sure you’re all grand. Regardless, I trudge on, talking to people about different ways to get by and dreaming of spaces where it might be easier to breathe.