CW: one extremely violent gif, some plot details from a big film from the ’90s

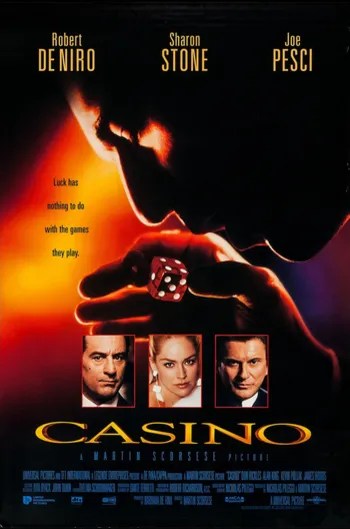

(Martin Scorcese, 1995)

Watched this at the GFT with some pals last night, having never seen it before. What can I say, I was a dumb Scorcese contrarian before it was popular, though I always had time for After Hours and Bringing Out the Dead, and anyway in the ’90s it felt like you were watching Casino whether you wanted to or not. Like a cocaine party, the chaotic egotism was in the air whether you were actually partaking of the stuff or just sitting in the corner like some other type of creep.

“Don’t fuck with me Al! Don’t make a fuck out of me! You wanna embarrass me, make a fool out of me, you didn’t gamble?”

This is such a lush film, so rich in its sound and vision, so slick in its editing, that it can feel ridiculous to focus on a couple of verbal riffs. Don’t worry – they’re part of the lushness too. So: I love the way that Joe Pesci’s Nicky uses language like he uses everything from a pen to his own brother – as a tool to fuck people up with. If the meaning gets bent out of shape with every blow – “Don’t make a fuck out of me!” – then he doesn’t mind so long as he can adapt and keep using his language as a weapon.

The rhythm of violence and acquisition is all Nicky is interested in, and he is so sure of his facility with it that he has no real sense of how his actions have bent his position within the mob power structure totally out of shape.

“But even if you bought him a really nice watch, one that he thought was nice, he doesn’t know what the fuck a good watch is. Say you go five, ten, twelve grand. At the most, which is impossible, for him. Plus, at the most, three suits, a thousand a piece. That still leaves what? Around ten thousand?”

As Ace, Robert De Niro leans into his own sour feature with a flatness of affect that is as loud as anything else in the film. The bad comedy of his exchange with Ginger when she comes back from her attempt to abscond with their daughter sees his own verbal tics at their peak, achieving a grim sublimity every bit as queasy as the way he wears his stomach ulcers on the outside, as a series of hot colours cooled down into pepto-pastels.

Two layers of Ace’s own character flaws stand out in this circular speech. First, his disgust at the fact that no one else in the world seems to weigh their bets as thoroughly as he does manifests in his inability to stop picking away at what Ginger is telling him about where the money went. Never mind the fact that Ace would be nothing if everyone else worked as joylessly on the details as he does, here as elsewhere in the film, his aggravation at other people’s sloppiness makes him incapable of taking an out when he sees one.

The second, deeper layer of this flaw comes through in his need to keep scratching away at the fact that Ginger would be with someone who doesn’t understand value as well as he does. The line “which is impossible, for him” lands in a slightly different register to the frequent mentions of “degenerate gamblers” from the mob lads, but it’s built on the same contempt for the realities of the scam these guys are living. There’s a fundamental confusion of success with virtue here, a misunderstanding of the fact that whatever his skills, Ace is only where he is because some old bastards who love to make money want him to be there.

“I went into this with my eyes open, you know. I knew the bottom could drop out at any time. I’m a working girl, right? You don’t think I’m gonna go into a situation like this if I don’t think I’m gonna get covered on the back end.”

Stone’s performance as Ginger starts off as pure fantasy then devolves to the point where it is one or two moments of blunt horror away from being an SNL wine mom skit. Both halves of this turn are spectacular, a tribute to the range she showed in her dominant era – Casino came out in the same year as The Quick and the Dead, in which she speaks a different language altogether. Like Ace and Nicky, Ginger seems sure of her command of the world she inhabits and has no idea how to operate when her real lack of agency is revealed to her. The difference here is that while the other two are free to narrate their expertise, and to run their respective fields, she is narrated into a corner halfway through the film and spends the rest of her time trying to reason with people in terms of the hustler’s code we are told she works by – having looked after people according to their needs, should she not be looked after in kind, whether that be in jewelry or murder?

Ginger is not the only character to refer back to deals made earlier in the film, only to find herself stymied by the implicit revelation that they were only part of the grift – the third act of Casino is full of these conversations. The fact that she has the most time to voice her booze-ravaged anger at the state of play makes her a better reader of the movie she’s in than she may appear while she is chopping up cocaine in front of her daughter while telling her she shouldn’t do the same.